Research

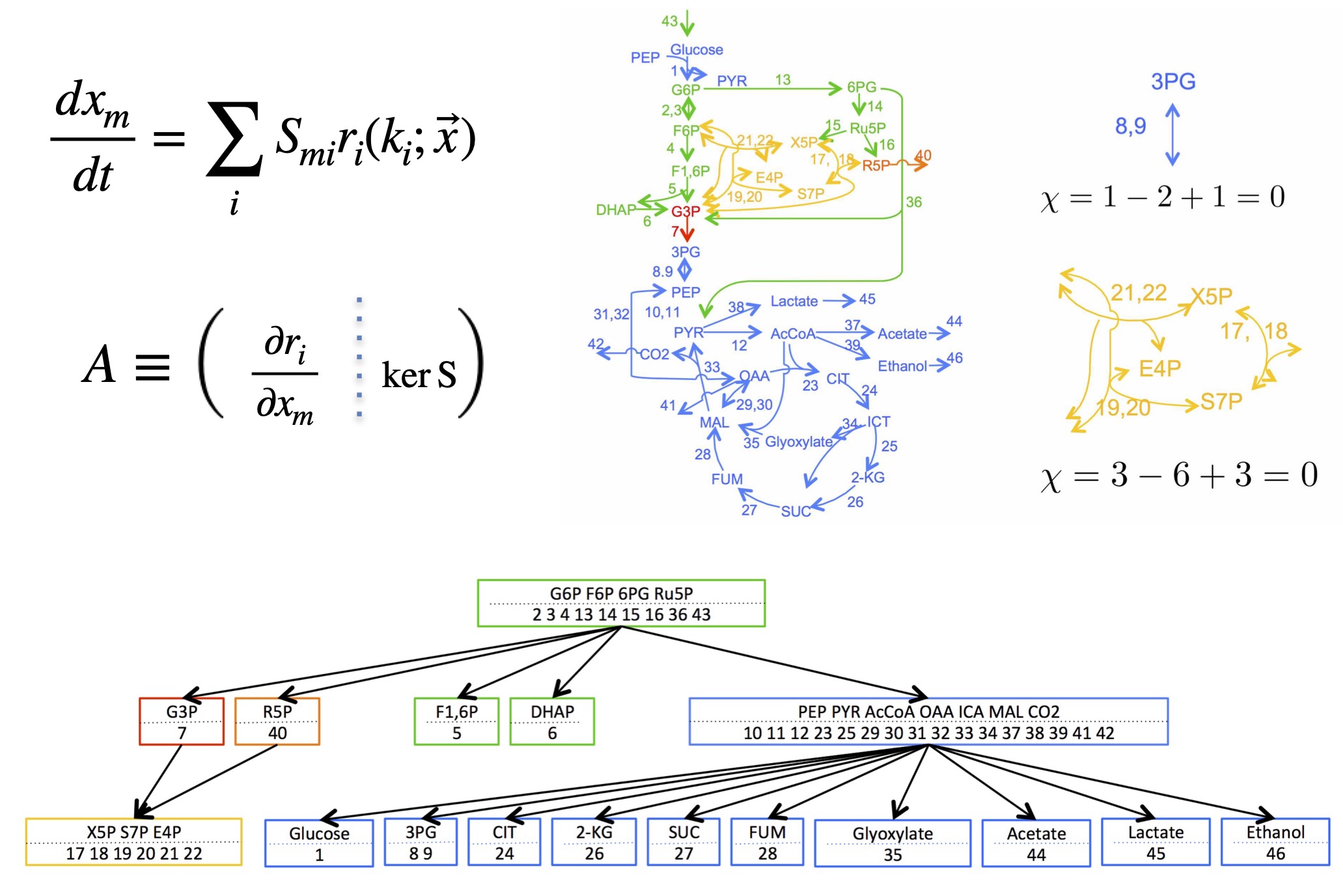

Network structure and control responses in chemical reaction networks

Inside cells, chemical reactions are connected by sharing the same chemical species (reactants and products), forming large-scale networks such as metabolic pathways.

In this research, we developed a theory that predicts—from the network connectivity alone—how metabolite concentrations and reaction fluxes at steady state change (i.e., sensitivities/responses) when enzyme activities are perturbed.

We found that nonzero responses exhibit two key properties:

Localization: For steady states, the effect of an enzyme perturbation does not spread across the entire network. Instead, it remains confined to a specific substructure (a buffering structure) characterized by a topological invariant analogous to the Euler characteristic: (# of species − # of reactions + # of independent cycles = 0).

Hierarchy: Buffering structures can be nested, which makes the influence propagate in a stepwise manner — “upstream → downstream”.

These results suggest that one reason biological systems are robust to external changes lies in the network structure itself.

We also showed that buffering structures govern not only perturbation responses but also bifurcation phenomena in chemical reaction networks (i.e., the diversity/multiplicity of steady states).

References

- Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 048101 (2016)

- Phys. Rev. E 98, 012417 (2018)

- Review article (J-STAGE, Japanese)

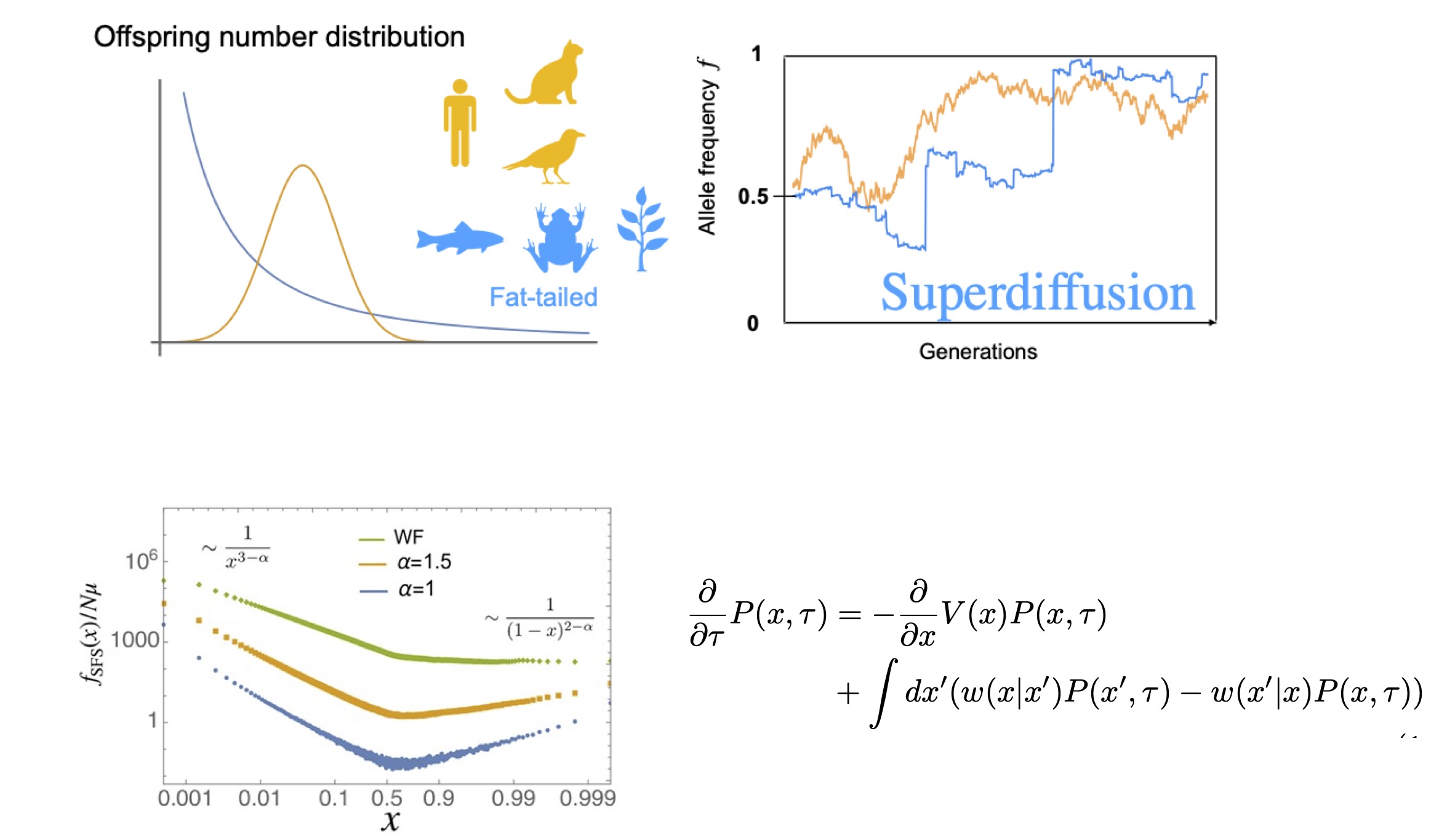

Interpreting evolutionary fluctuations: a new theory driven by skewed offspring distributions

In many natural populations, individuals differ greatly in the number of offspring they leave. While most individuals leave few or no offspring, a small fraction can leave an exceptionally large number. In such situations, allele frequencies can fluctuate strongly due to chance—this is known as genetic drift.

However, classical population-genetic models often assume that the variance in offspring number is not too large, and therefore they cannot fully explain the large fluctuations observed in real populations.

In this work, using asymptotic analysis and scaling arguments, we showed that in populations with extremely broad offspring-number distributions, a natural bias against minority alleles can emerge.

This bias arises because the contribution of the “most prolific” individual in each generation fluctuates over time. As a result, this new bias competes with standard evolutionary forces such as selection and mutation, producing allele-frequency fluctuations that differ qualitatively from the classical picture.

Moreover, we derived simple scaling relations for the magnitude of allele-frequency fluctuations, fixation probabilities, times to extinction, and the resulting allele-frequency spectrum.

Such non-classical evolutionary laws are now beginning to be observed in fast-evolving populations such as microbes and viruses. Because these systems allow direct observation of evolutionary dynamics in laboratory evolution experiments, they offer promising opportunities to test theory–experiment connections.

References

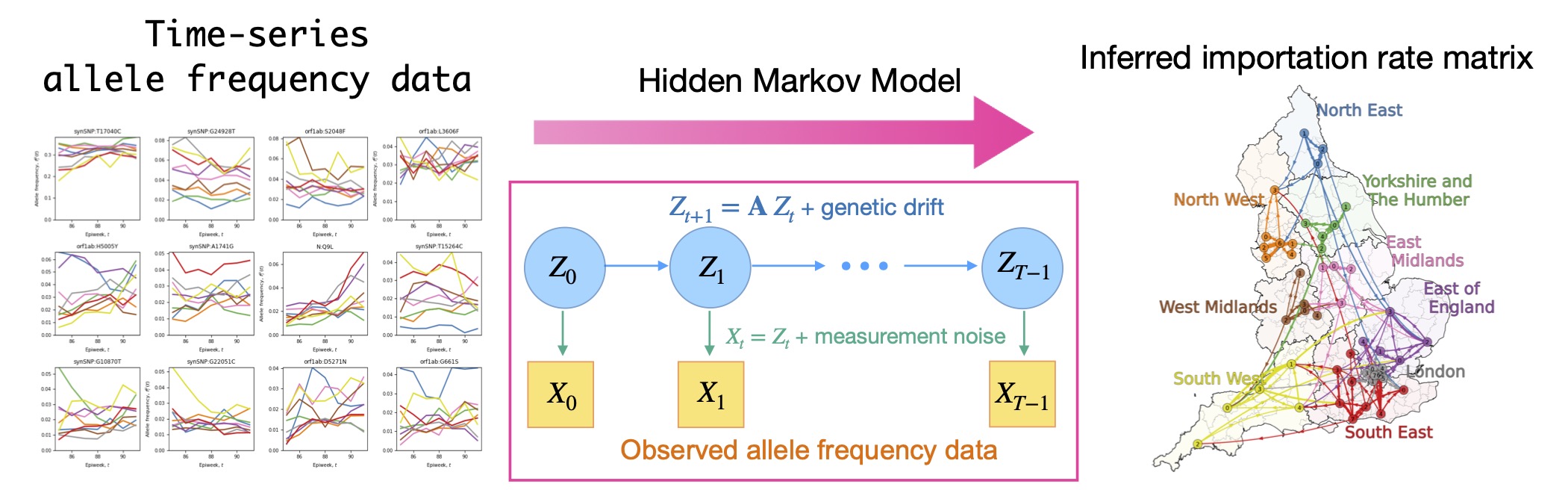

Inferring Viral Transmission Pathways from Allele Frequency Time-Series Data

The COVID-19 pandemic has renewed awareness of the importance of interregional transmission, namely how pathogens spread across geographic regions. Traditionally, transmission has been inferred from human mobility data and contact histories; however, it has been difficult to capture rare transmission events occurring between socially or geographically distant regions.

In collaborative work with G. Isacchini, Q. Yu, and O. Hallatschek (University of California, Berkeley), we developed a mathematical method to directly infer importation transmission rates between regions from time-series data of allele frequencies. To account for observation errors and stochastic fluctuations in allele frequencies, we employed a hidden Markov model.

Applying this method to SARS-CoV-2 data revealed not only how interregional infection networks change across viral variants, but also the time scales over which transmission occurs and how transmission speeds differ between regions.

This study opens a new avenue for genome-based time-series analysis and is expected to contribute not only to future epidemiological monitoring and predictive models of pathogen spread, but also to a wide range of applications. The study was published in PNAS (2025) and also highlighted as a promising approach in a PNAS Commentary.

参考URL / References

- Plos Pathogens 20.4, e1012090. (2024)

- PNAS 122 (48) e2500663122 (2025)

- Featured in a PNAS Commentary.

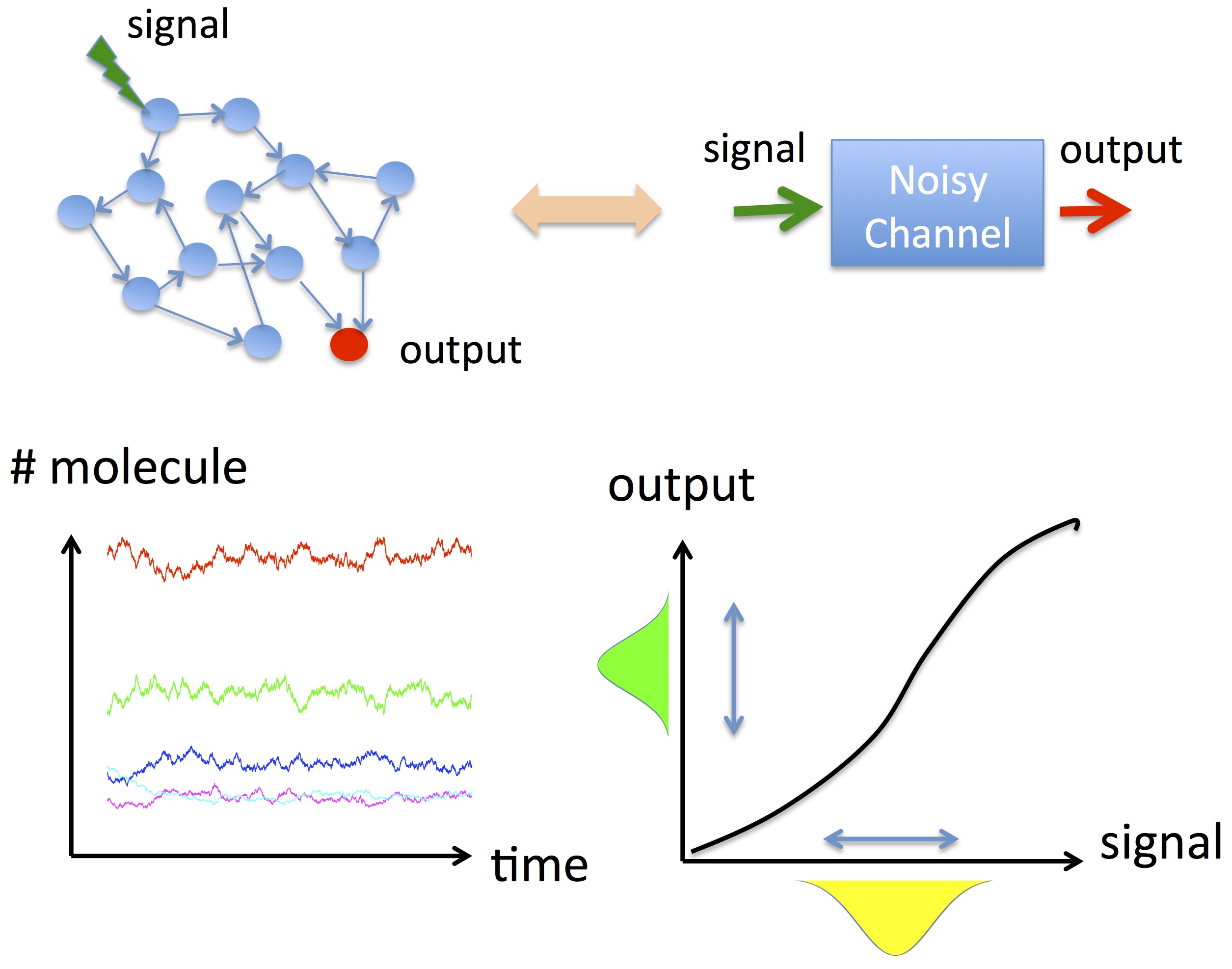

Information transmission in control networks

Accurate information transmission is a fundamental property shared by biological, social, and technological networks. Transfer entropy is a widely used measure that quantifies information flow, but even for small networks it often requires numerical computation, making it difficult to understand why information transmission works well.

In this research, focusing on stochastic Boolean networks, we derived a diagrammatic formula that allows transfer entropy to be computed analytically. The method applies to networks with arbitrary intermediate structure between an input signal and an output node, and also allows each node to implement a different logical function.

By decomposing transfer entropy into contributions from individual network components, we clarify which pathways carry information and provide design principles for network structures that maximize information transmission.

These results are applicable to understanding and designing real-world networks, from biological systems to engineered artificial networks. We are currently extending this theory to observational data and real networks, aiming to analyze information transmission directly from empirical measurements.